The law of least effort says that when a task can be solved in several different ways, over time, people gravitate towards the one that requires the least effort. Considering this theory, it makes sense that nearly everybody uses artificial intelligence to save time and effort. But that’s not the full story. This law does not tell us that completing a task in the way you have the least resistance is always the best way. It only describes a recurring phenomenon.

AI can easily automate many tasks like summarizing reports, drafting emails, generating creative ideas, writing letters to customers, and so on, but the question is which tasks are better off being automated by AI and which are not?

The Longer Way is Shorter

Take, for example, college students who have to write an essay. Many of them use AI for the majority of their writing process. I’ve done it myself, too. It makes sense; students use AI because it frees up so much time. AI is a free page-filler machine. But everybody knows that the world is not waiting for more college student essays; in fact, nobody cares about them. The only reason students need to write essays is to develop skills like critical thinking.

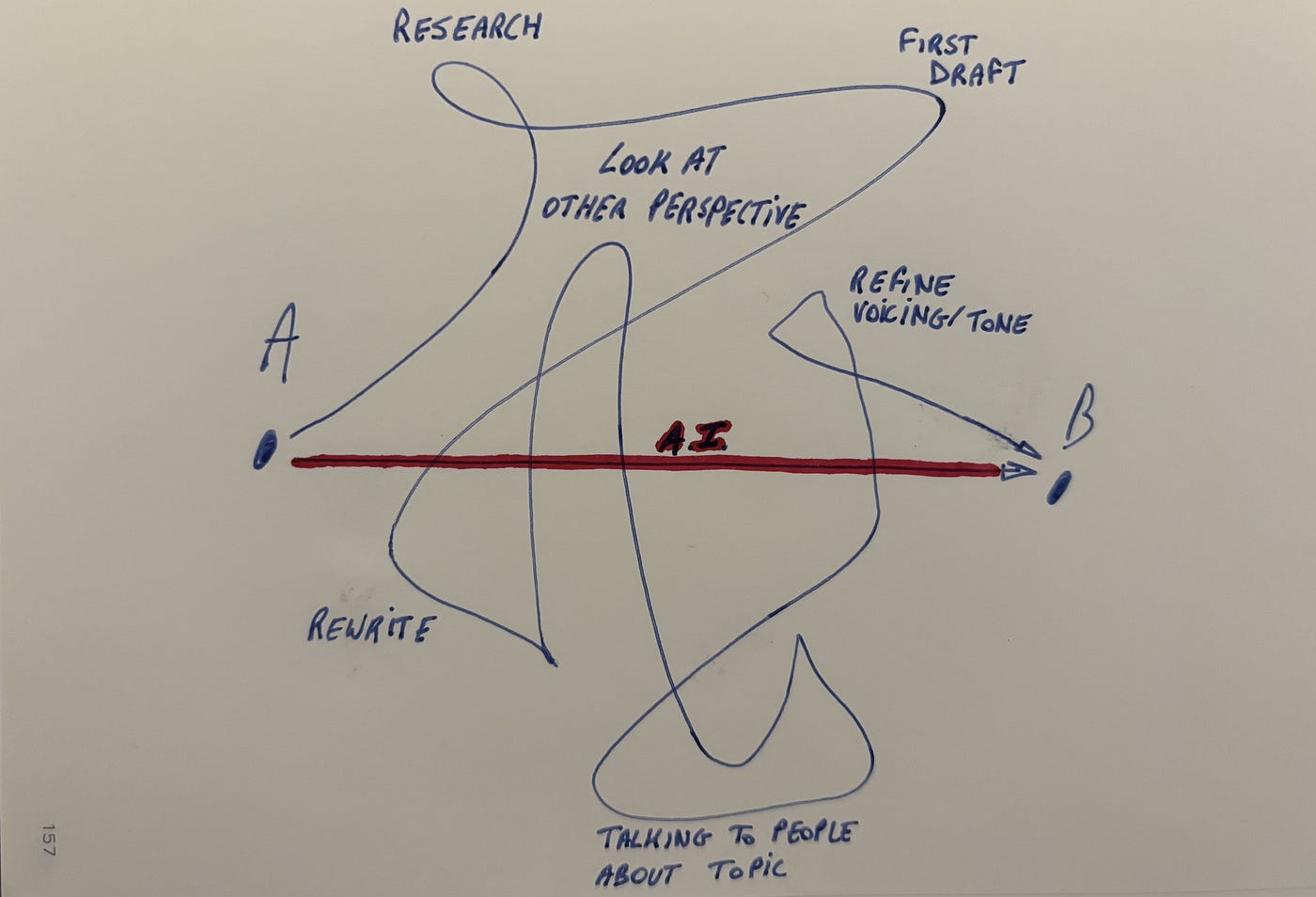

The process of writing is: (1) gathering data and ideas; (2) processing and merging them logically together; and finally (3) writing them out. AI can replace all three stages. That is concerning. It’s like someone takes a plane from San Diego to New York and then pretends to have seen the entire United States. You save time, yes, but you miss all the valuable things along the way. By car, you might sometimes drive the wrong way, and it would certainly take much longer, but you would learn and remember a lot from the experience.

I’m convinced that at the end of the day, the longer way is shorter.

The feeling of hard work

About a week ago, a friend told me he was writing his thesis and had already committed thirty pages of text to paper. Almost instinctively, I asked him if he wrote that all himself. His answer sounded so profound to me. He said, “Of course I did; how could I ever feel proud of my thesis if I didn’t put in the work myself?”

I never really thought about it that way. Finishing an AI-generated text that you tried to humanize feels like hiding a crime; you hope nobody discovers it. You cannot enjoy the result. On the other hand, there is no better feeling than writing something yourself, working on it for days, and then finally handing it to the world. In the end, hard work is an essential element for our well-being and happiness.

The authentic salesman

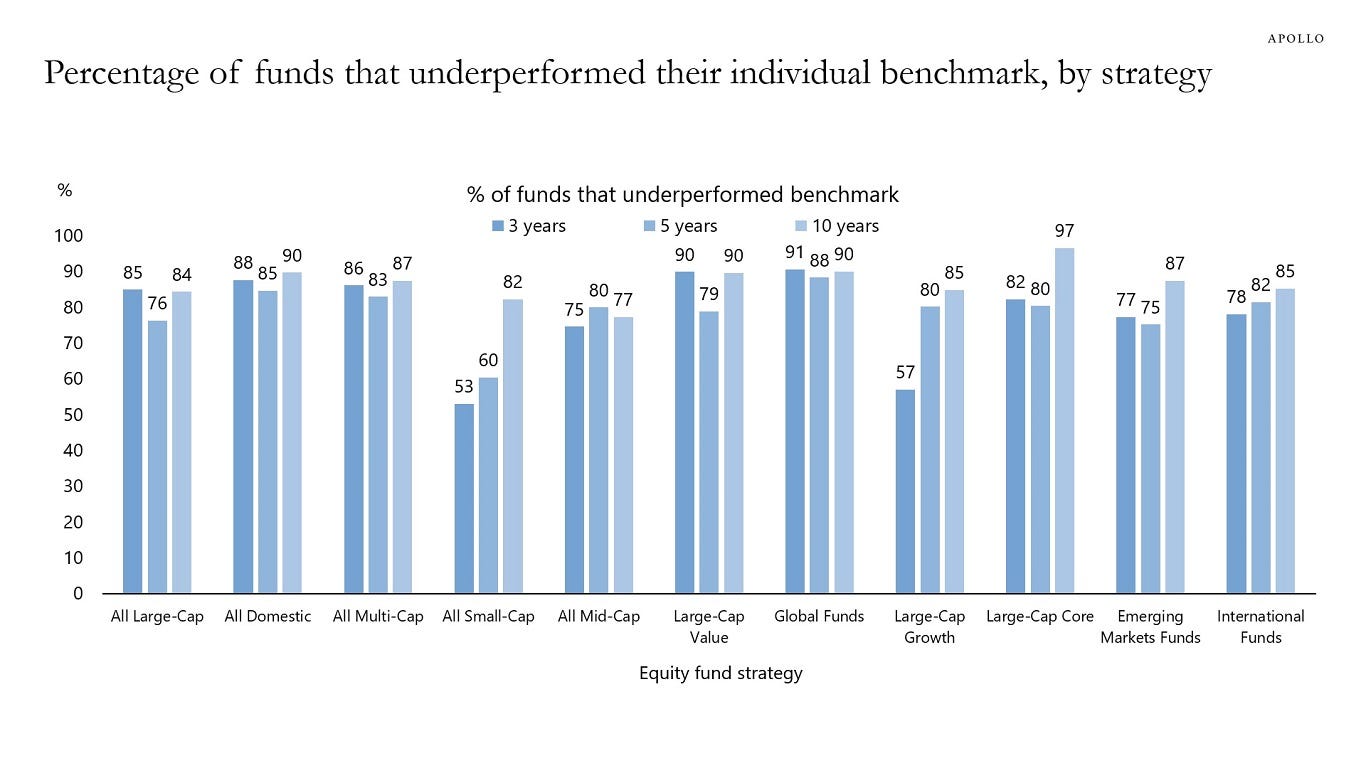

As more and more people and students use AI for their emails and essays, it becomes increasingly easy to stand out with your self-written work. Generated texts all have the same format, language, and style of writing. That is because AI models don’t make any creative decisions. I was confused when my professor of data science told us one day that LLMs (Large Language Models) like ChatGPT only predict the next word in a sentence based on a large training set. No wonder generated texts all look so similar.

I might be wrong; time will tell, but I truly believe that authentically written texts will be praised and cherished the more people use AI. Imagine a procurement department receiving dozens of AI-generated emails a day, while suddenly they receive an email from a salesman with a small personal anecdote from their last meeting together. Which email will have the greatest impact, you think?

People love that intimate, personal connection, which AI simply cannot provide.

The verdict

Many tasks could be automated by AI. Especially those tasks that normally don’t require us to make lots of decisions: transferring data between platforms, generating invoices, sending automatic payment reminders, and so on. There is no doubt that AI can enhance productivity. My point, however, is that not every task that can be automated gets off better when automated. When automating a task that requires lots of decisions, like writing an essay, quality and authenticity inevitably get lost.

Not using AI means falling behind; using AI for everything transforms us into thoughtless robots. A solution to not belong to either side is to use it intentionally. Is this task better off by using AI, or should I put my brain to work to produce something creative, personal, or original? Our brains can make out-of-the-box decisions that no AI tool can, and we should use this to our advantage.

Doing something in the least effortful way possible is not necessarily the best way.

“Responsibility to yourself means refusing to let others do your thinking, talking, and naming for you; it means learning to respect and use your own brains and instincts; hence, grappling with hard work.” — Adrienne Rich